UK Budget: higher growth, spending and taxes

Any Budget needs to be judged in the context of the time. This is particularly the case for this Budget, in the wake of a pandemic and also in the context of an economy whose trend of growth has still not recovered from the hit of the 2008 global financial crisis.

Also, the challenges confronting the UK are not unique: global public debt is at an all-time high, cheap money policies are feeding financial risks and inflationary pressures are building across the globe. Add in the uncertainty of the pandemic, which weighs on confidence, and one can understand that there is still considerable uncertainty about the outlook for the economy and public finances.

It was against this backdrop that the Chancellor unveiled a generous Budget in boosting public expenditure, which when considered alongside fiscal measures announced in recent weeks which were unnecessarily tough in raising taxes, provides a significant fiscal injection in coming years. As a result, in the words of the Official of Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) report that was released alongside the Budget, there has been a “permanent increase in the size of the post pandemic state”.

Meanwhile, recent tax changes have raised the tax burden from 33.5% of GDP in 2019/20, before the pandemic, to 36.2% in 2026/27, the highest since the early 1950s. The most significant tax changes impacting over the next year are the freezing of the income tax threshold which was announced in a previous Budget and the recently unveiled rise in the national insurance thresholds.

Given this, there are a number of takeaways from the Budget:

- First, the economy and public finances have turned the corner, with a rebound in growth and falling government borrowing. The OBR’s assessment is that, “borrowing is lower in every year than forecast in March.” In turn, future gilt issuance will be lower than expected. Despite this, the economy and public finances remain in a fragile state, vulnerable to further shocks.

- Second, this was a mildly stimulative Budget that provided a fiscal boost to the economy - while tax increases will squeeze demand, there is an even larger rise in spending.

- Third, the key is economic growth. The Chancellor spoke about an age of optimism, but the government now needs to deliver upon pro-growth supply-side polices to help deliver it. This will need to include a host of measures including incentivising the private sector. I still think there is a need for a pro-growth economic strategy.

The economic numbers

The OBR’s economic projections have been too pessimistic and, in turn, the margin of error on their budget deficit forecasts has been significant. Now, they see the economy growing 6.5% this year (versus their forecast of 4.1% in March) and 6% next. This would allow the economy to return to its pre-crisis level around the turn of the year. The OBR noted, in particular, higher labour income and rising consumption in coming years.

Of course, there are immediate challenges, with the economy having lost momentum recently, growing by 2.9% in the three months to August versus 5.5% in the three months to June. Health issues continue to weigh on confidence. There are also concerns about an imminent squeeze on the cost of living because of higher inflation, rising energy costs, possible rises in mortgage rates and higher taxes.

Another challenge is what happens from 2023 onwards. Growth is expected to decelerate to 2.1% in 2023, followed by 1.3% (2024), 1.6% (2025) and 1.7% in 2026.

Perhaps the clearest evidence of the growth challenge is seen in the figures for GDP per head. After falling a massive 10.2% last year and then recovering by 6.3% this year and 5.6% next, the pace slows to 1.7% in 2023, 1.0% in 2024, 1.3% in 2025 and 1.4% in 2026.

The OBR remains cautious about any post-Brexit growth dividend – they still expect it to dampen trade prospects – and thus the challenge, perhaps, for future Government policy is to show that there is scope to raise the future trend of growth; it has fallen significantly since before the 2008 global financial crisis.

One significant aspect of the last year has been that the furlough scheme helped prevent unemployment from reaching anywhere near the rates once feared at the start of the pandemic. Unemployment, according to the official forecasts, will peak at 5.4%, not the initial 12% feared.

Budget numbers

The margin of error on budget projections is high, and the lesson is that stronger economic growth can allow the public finances to improve significantly. Indeed, the deficit over the first half of this fiscal year is already £43.5 billion better than forecast in March, because of the stronger rebound. Even so, the OBR sees the budget deficit for the whole fiscal year coming in “only” £51 billion better than they thought in March, with the deficit expected to almost half to £183 billion. Perhaps the outcome may prove better.

Against this backdrop of an improving economy and public finances, the Chancellor felt he had both the room and the need to intervene. Table 5.1 of the Budget Red Book pointed to a sizeable 65 policy decisions that contained an expenditure or tax implication, including the measures announced in recent weeks such as the health and social care levy. This is considerable, and while many measures were welcome, it suggests that this was a very interventionist Budget.

Welcome measures included a reduction to the taper on universal credit, helping those on low income and a reform to the taxation of alcohol. The Budget also laid some of the groundwork for the key joint political and policy areas of the green agenda and levelling up.

There has been some criticism that the green agenda did not receive enough attention, yet the Red Book points to a “green spend” totalling £5.3 billion in 2021/2, £6.5 billion in 2022/23, and higher in following years. There were also a host of measures linked to levelling up.

The Chancellor also confirmed the pre-Budget announcement of an increase in the national living wage. This move, though, particularly in the wake of the hike in national insurance, reinforces the need to reduce future business costs, including tax and regulations, particularly for small firms.

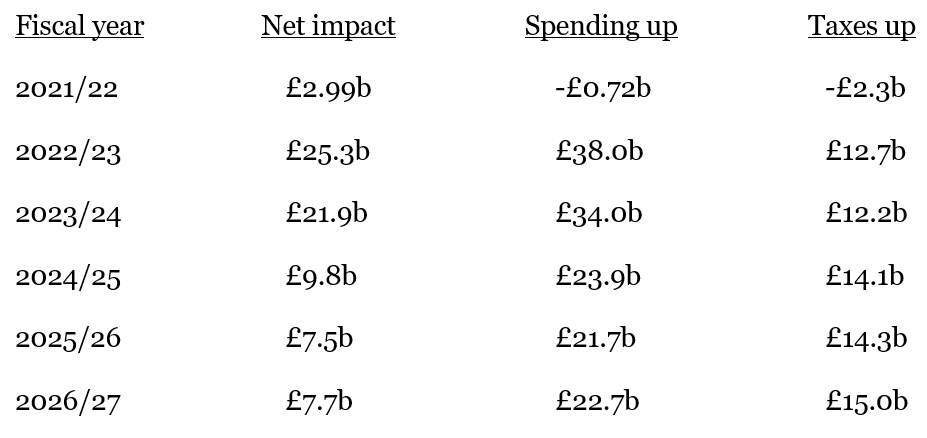

The net result was that this was a stimulative Budget as the boost to spending exceeded the hike in taxes. The information in the table below is the effect of the 65 policy decisions identified in Table 5.1 and highlights the net boost provided by recent fiscal measures. In 2022/23 there will be a net boost of £25.3 billion, reflecting £38 billion higher spending partially offset by £12.7 billion in higher taxes. Notably, departmental spending and the tax take are set to rise significantly in coming years.

These figures are compiled from Table 5.1 of the Red Book. The net impact shows the net fiscal boost.

Importantly, the Chancellor announced some new fiscal rules, aimed in part at ensuring that he keeps the financial markets on side about his commitment to improve the public finances. I have been sceptical in the past about fiscal rules, as they usually don’t stand the test of time. On this occasion, however, it was welcome that the focus was on reducing debt to GDP, gradually over time. This makes sense. Debt to GDP, after peaking at 98.2% in 2021/22 is expected to fall to 88% by 2026/27.

In a competitive global economy, the UK needs to increasingly compete with the faster growing economies from the Indo-Pacific, including the US and the economies of east Asia. The worry is that it is replicating more, not so much the high tax and spend of the UK’s past, but a similar model to that of Western Europe, the region suffering from ongoing sluggish growth.

A bigger scientific base and innovation is one UK aim that is clear, and welcome, but increased public spending should go hand in hand with much needed reforms in many areas to deliver both better public services and economic outputs. Planning reform is just one example, and the dilemma in the wake of this Budget is that increased public spending must not prevent the tax cuts and lower business costs needed to allow the private sector to grow.

That requires an immediate policy focus on necessary supply-side change. It needs a clear pro-growth vision which investors as well as the public understands. The UK needs to become even more attractive for business investment and that is hard if the tax system is not internationally competitive with a clear policy direction.

Inflation risk

The immediate reaction to the Budget appears to have been a mix between positivity about such an accomplished performance and concerns that we have moved to an era of high rate of tax and spend.

The biggest risk to the Budget numbers is that growth disappoints, either in coming months because of health fears or a cost-of-living squeeze because of higher inflation and increased taxes and energy costs, or because the post-pandemic rebound gives way, as noted above, to even weaker growth than is already factored in.

While the economy and public finances may have turned the corner, both are still vulnerable to shocks, and this was reflected in the Chancellor’s focus on inflation so early on in his speech.

The current rise in inflation is unlikely to prove permanent, but it may persist, as opposed to pass-through quickly, not helped by the Bank of England’s stance to date. The persistence of inflation not only threatens a squeeze on living standards, but also, as the Chancellor alluded to, adds to borrowing costs through higher interest rates or yields.

What does this mean for the Bank of England next week? The Monetary Policy Committee voted 9-0 to leave rates at 0.1% last time they met. Since then, some members, including the Governor, have given hawkish statements. As a result, and given the inflation outlook, the market expects a hike next week. My preference is still for the Bank to exit via tapering – namely stopping and reversing QE – as opposed to tightening via higher rates. Yesterday’s Budget is unlikely to have changed the hawkish bias of next week’s meeting, with a rate hike likely.

Economic growth

One of the issues I have highlighted is the need to boost growth through supply-side measures, covering areas such as innovation, investment and infrastructure spending as well as incentives, with the latter reflecting the need to lower taxes and ease regulations.

The Budget leaves growth, taxes and government spending higher. There is a near-term challenge in terms of inflation, and a possible cost of living squeeze. Thus, the economy faces an immediate vulnerability and a longer-term challenge about the pace of future growth. The key message after this Budget is the need to ensure stronger sustained growth.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.