The good news is inflation should fall, but it is still unclear where it will settle

As we look towards 2023 it already looks set to be the year of the good, the bad and the uncertain.

The good being that inflation will decelerate. The bad being that growth will weaken, with recession set to hit a host of countries including the UK. The uncertain being that it is unclear by how much inflation will decelerate, how high interest rates will rise to, or how fragile growth, property prices and financial markets, including corporate earnings, will prove to be in this economic climate. Challenging times lie ahead.

Let’s focus here on inflation. It is only a few weeks ago that markets globally and – particularly in the UK – were in a febrile state. At that time, worries about inflation were centre stage, with markets fearing that central banks were either behind the curve (particularly in the case of the UK), or were set to tighten aggressively (led by the US Federal Reserve). Then, in addition here, the clumsy approach of the new Truss government exacerbated this, feeding the idea of a dash for growth led by tax cuts, triggering a short-lived market crisis and fiscal policy reversal.

But in recent weeks the mood of global markets has shifted, for a variety of reasons. There is now, generally, an expectation in markets that covers three broad areas: one, that inflation has peaked, and is set to decelerate; two, that while global growth will weaken, the markets are acting as if they have discounted this; three, even though interest rates are yet to peak this will not be as high as markets previously feared and that if growth weakens too much, then it will be possible to ease monetary policy.

One might genuinely ask whether such wishful thinking will materialise? After all, it suggests healthy earnings growth, low peak policy rates and lower bond yields than previously thought.

Additionally, prospects of an early ending to China’s zero Covid policy has also helped global market sentiment. For much of this century, China has accounted for close to two-thirds of the increase in global growth. The hope is that this policy shift will see China’s economy recover, helping the global outlook. But, equally, a rebound in China has the ability to trigger higher non-oil commodity prices, perhaps limiting the pace at which inflation may decelerate globally.

Markets, naturally perhaps, distil the information and cut straight to the chase. Take the US as an example. After the recent speech by Fed Chairman Powell, the market reaction was to focus on the likelihood that the immediate pace of policy tightening would slow. At recent Fed meetings, hikes were 0.75%. Now a 0.5% increase is expected in December.

But alongside hinting at this, the crux of Powell’s message was that policy still had to tighten further to curb inflation, and that once rates reach their peak they might stay there. In essence, the markets think US rates can peak at not too high a rate and then come down subsequently, expecting a peak around 5% next May, with rates then falling before the end of 2023. Powell seemed to be saying they will plateau, not peak.

One of the immediate focuses of attention is peak inflation, with the market view that inflation will decelerate and return to relatively low levels. After all, supply-chain pressures have eased, monetary policy has already tightened in many countries, and economies are already slowing.

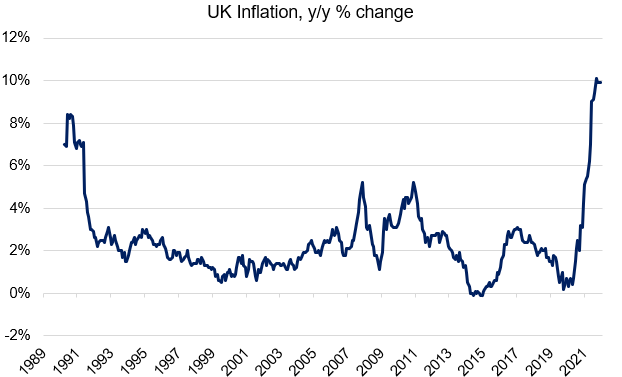

Let’s focus on the UK. Consumer price inflation has risen steadily from a low of 0.7% in February 2021. By the time Russia was invading Ukraine in Feb 2022, UK consumer price inflation was already 6.2% and retail price inflation already at 8.2%. Now, consumer price inflation is 11.1%. This should be the peak.

Source: Office for National Statistics.

The two factors that fed inflation, namely lax monetary policy and supply-chain pressures are now being reversed. Monetary policy is being tightened in the UK and most western economies. The market expects UK policy rates to rise from their current 3% to peak at 4.5% before next summer.

Given how weak growth is, and that quantitative tightening is also occurring, it may be the case that policy rates do not rise that far. As we have stated before, the speed, scale and sequencing of monetary policy tightening needs to be sensitive to the economy’s performance.

Supply chain pressures have eased. Also, oil prices are significantly off their peak. Commodity prices are likely to decelerate. But the outlook for non-oil commodity prices is very uncertain, as with China reopening this is likely to boost growth in China and across Asia, and previously this has pushed commodity prices up. This time, it may limit the extent to which they fall.

The risk is that often it requires much tougher monetary policy to curb inflation once it has risen. In the 1970s, when inflation rose, and in the early 90s, when inflation decelerated, expectations were slow to adjust to the new inflation landscape. That is worth bearing in mind now.

Much may depend upon second-round inflation effects, such as the extent to which wage growth rises, or the extent to which firms are able to boost profit margins. But with growth slowing and inflation decelerating, this explains why markets expect policy rates (in the US and euro area as well as the UK) to peak far below current rates of inflation.

The latest HM Treasury survey of inflation forecasts shows that in November private sector forecasts now expect CPI inflation to decelerate from 10.5% in Q4 this year to 5.0% in Q4, 2023. But only in October, similar forecasts pointed to inflation decelerating to 4.1% by Q4, 2023. This highlights how expectations can change, heavily influenced by views about energy prices, or future policy.

Also, in its November Monetary Policy Report, the Bank of England made the following forecasts for CPI inflation (their forecasts from August are shown in brackets): 10.9% (13.1%) in Q4, 2022; 5.2% (5.5%) in Q4, 2023; 1.4% (1.4%) in Q4, 2024; and 0.0% in Q4, 2025. Essentially, the Bank expects inflation to decelerate towards its 2% inflation target in two years and to undershoot it in three.

Although as the previous Governor Mervyn King pointed out earlier this year, inflation was always expected to return to 2% in forecasts, often for no other reason than that was the target.

Interestingly, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) November forecast, “Inflation drops sharply over the course of next year and is dragged below zero in the middle of the decade by falling energy and food prices before returning to its 2 per cent target in 2027.” Indeed, conditional on market expectations for policy rates and gas prices, the OBR expects inflation to fall below zero for eight quarters from mid-2024.

It is worth keeping in mind the views of monetarist economists, who generally were cautious about inflation before the latest surge, highlighting that inflation follows from excess money and that central banks in the US, UK and euro areas created excess money in 2020-21. Now, excess money is being eliminated, and with monetary growth decelerating, one might perhaps ask whether there is a need to now guard against the risk of over-tightening by central banks.

It is a similar challenge at a global level. Take the International Monetary Fund (IMF) measure for advanced economies consumer price inflation. This has been relatively low over the last decade. In 2020 it was 0.7% and 3.1% in 2021. The IMF expects 7.2% this year and 4.4% in 2023. And as a future indicator they predict 1.9% by 2027.

So, like the UK, decelerating this year and next, and then reaching around an expected 2% rate. For emerging economies, the IMF sees inflation lower than in the west this year (at 4.1%) and next (at 3.6%) with a forecast of 2.8% by 2027. The overall picture is a return to low inflation.

While a deceleration in inflation is already factored in, over the next year and into 2024, it is still far from clear where it will settle and whether it settles at a higher level post pandemic than prior. There are still large post-pandemic variations within countries as to how people are being impacted by the cost-of-living crisis, as well as across countries themselves. All of this will impact second-round inflation effects as economies slow. This we will focus on next week – when we look at growth prospects for 2023.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.