For investors, this evolving landscape presents both risks and opportunities. This article examines the challenges, policy responses, and the investment potential of Chinese equities, with a particular focus on onshore China A-shares.

China’s economic backdrop

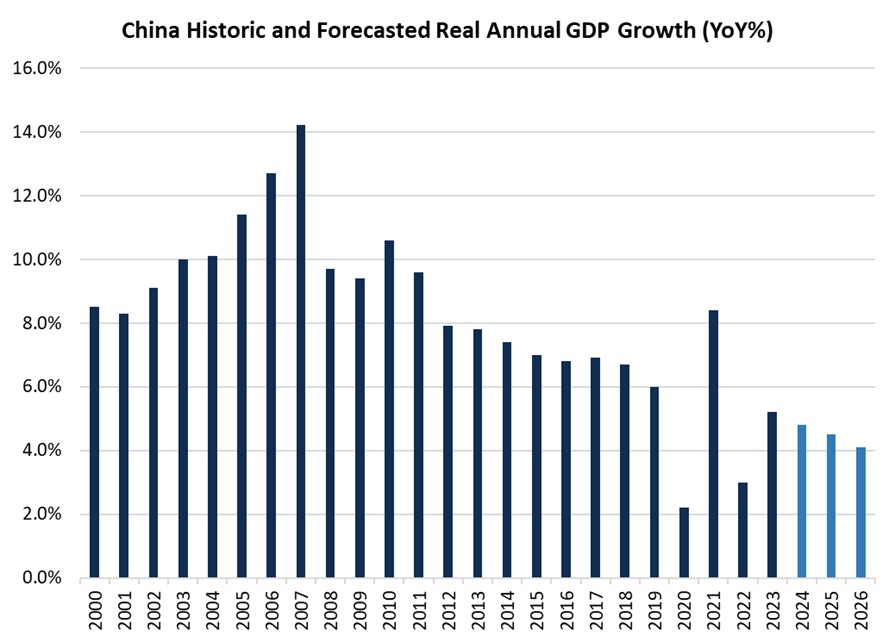

Structural changes have seen China's economic growth expectations moderate significantly during the last decade. A decade ago, the focus was on avoiding the middle-income trap – where a country’s income rises to the point where it is not competitive compared to other nations, and essentially stagnates. Since its opening up at the end of the 1970s China had moved from low to middle income, but the challenge was to avoid remaining there and to move to higher income.

Source: Bloomberg

Between 2000 and 2010, the economy expanded at an average annual rate of 10%, driven by industrialisation, urbanisation, and export-led growth. However, following the Global Financial Crisis between 2007 and 2009, growth rates began to slow down, averaging around 6-7% annually between 2011 and 2020. The government shifted its focus towards domestic consumption, innovation, and sustainable development during this period.

In the post-pandemic era, after an initial strong rebound driven by pent-up demand and government stimulus measures, growth slowed again due to prolonged COVID-19 regulations (Zero-COVID policy) and weaker global demand. Coupled with a property sector crisis, this has prompted Chinese policymakers to moderate their annual growth target to 5%.

China's recent property sector crisis, which emerged around 2020, has exposed significant economic vulnerabilities. Triggered by overleveraging, overbuilding, tighter debt regulations, and falling property prices, the crisis came to a head when major developers like Evergrande defaulted in 2021, uncovering deeper systemic issues.

The crisis could be characterised as a balance sheet recession – where high private sector debt forces companies and individuals to prioritise debt repayment over spending or investment. In the property sector, developers burdened with substantial debt have shifted their focus to managing liabilities and completing existing projects rather than launching new ones.

This has led to sluggish economic activity, reduced investment, and stagnating growth, as expansion gives way to financial caution.

Compounding the crisis are broader challenges, including high levels of private and local government debt, declining consumer confidence and private investment, an ageing population, and severe youth unemployment. Rising geopolitical and trade tensions further cloud the outlook, leaving policymakers to navigate immediate financial instabilities while pursuing long-term reforms to restore sustainable growth.

Policy measures: a response to economic pressures

With China's economy moderating for some time, critics argue that policymakers have been too slow to implement bolder measures to stimulate the economy. In the third quarter of 2024, GDP growth was recorded at 4.6%, with growth averaging 4.8% over the first three quarters of this year. This slowing momentum indicates a real risk of missing the already moderated 5% growth target.

Furthermore, falling prices have also raised concerns about deflation. As of October 2024, China's annual inflation rate stood at 0.3%, well below the government's target of 3% for the year. These challenges – combined with the US Federal Reserve’s decision to begin normalising monetary policy rates with an outsized 0.50% interest rate cut in September – prompted Chinese policymakers to introduce a comprehensive set of stimulative policies dubbed “China’s monetary bazooka.”

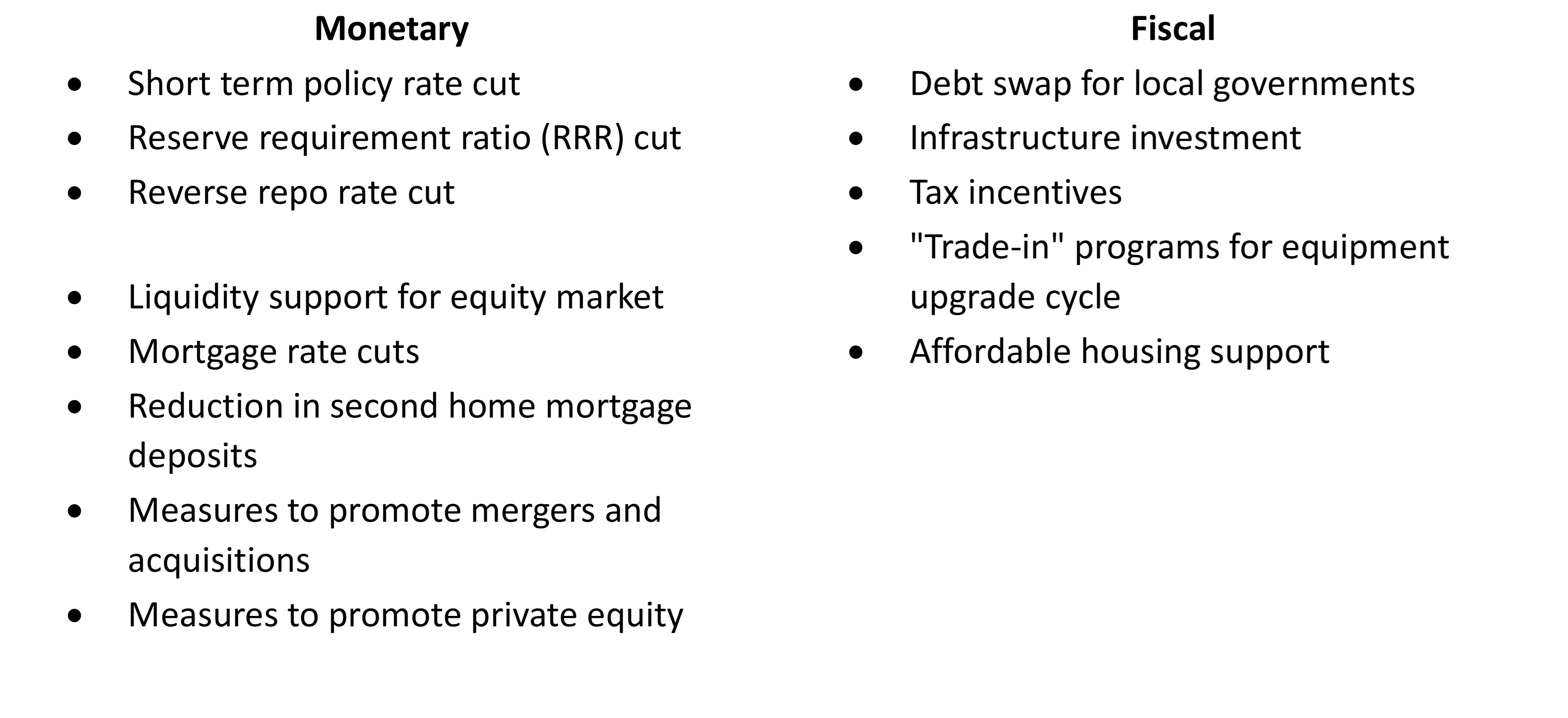

The monetary measures included efforts to expand credit availability, lower borrowing costs, enhance liquidity, support the stock market, and reduce mortgage rates. However, many analysts believe that fiscal measures are essential to complement these actions and to stimulate consumer demand. Consumers, burned by losses during the recent property crisis, may prioritise saving instead of spending or investing, limiting the effectiveness of monetary easing alone.

Fiscal measures announced so far have been targeted at vulnerable sectors and include a $1.4 trillion debt swap programme to help local governments and a range of specific measures to stimulate the housing market. While these fiscal initiatives signal progress, they have not yet fully instilled the market with confidence that Chinese policymakers will do enough to reaccelerate the slowing economy.

China’s recent stimulus measures

Early signs, however, indicate that these stimulative actions are beginning to bear fruit, and stabilise the Chinese economy. Recent improvements in export figures, business confidence, corporate investment intentions, retail sales (particularly durable goods), and housing activity suggest that growth may be troughing.

In December, the annual Central Economic Work Conference will outline the key policy areas ahead of the Two Sessions next March. Building on the third Plenum's summer focus on structural reforms, these discussions will shed more light on policy direction.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has also adjusted its monetary policy focus, introducing “reasonable price increases” as a new additional monetary policy target. This highlights that Chinese policymakers view outright deflation as a substantial risk, arguably opening the door for further easing.

Policymakers are carefully monitoring signs of economic recovery while weighing the relative stance of their monetary policy. If it is perceived as excessively accommodative compared to international counterparts, it could result in significant weakening of the Chinese yuan. Such currency depreciation may not only disrupt economic stability but also risk undermining political confidence and social stability. This may prompt a more measured and strategic approach.

Further to this point, Beijing may seek to avoid overly aggressive or premature easing to conserve policy tools for potential geopolitical risks, such as escalating trade tensions with the United States.

Geopolitical challenges and trade tensions

Geopolitical tensions remain a key risk for China’s economic outlook. In recent years China has faced tariffs and sanctions. Tariffs in the first Trump term led China to seek self-sufficiency in areas such as food, energy and technology, with the latter being hit by sanctions in recent years. China has moved into green technology and electric vehicles (EVs), although its success in the latter has led the EU to impose tariffs on EVs recently.

Projections suggest that China’s trade surplus could reach a record $1 trillion by the end of 2024, intensifying scrutiny of its trade practices. It is anticipated that US tariffs on Chinese exports could be increased to around 60% for certain products.

China will come under increased pressure under a second Trump presidency, with the Republicans achieving a “clean sweep” (winning the presidency and gaining control of the Senate and the House of Representatives) in the US election. This is further underscored by the appointments of China ‘hawks’ to prominent positions in Trump’s administration, such as Mike Waltz as National Security Adviser and Marco Rubio as Secretary of State. Both of these lawmakers are known for their strong positions on China’s influence.

The investment case for China A-shares

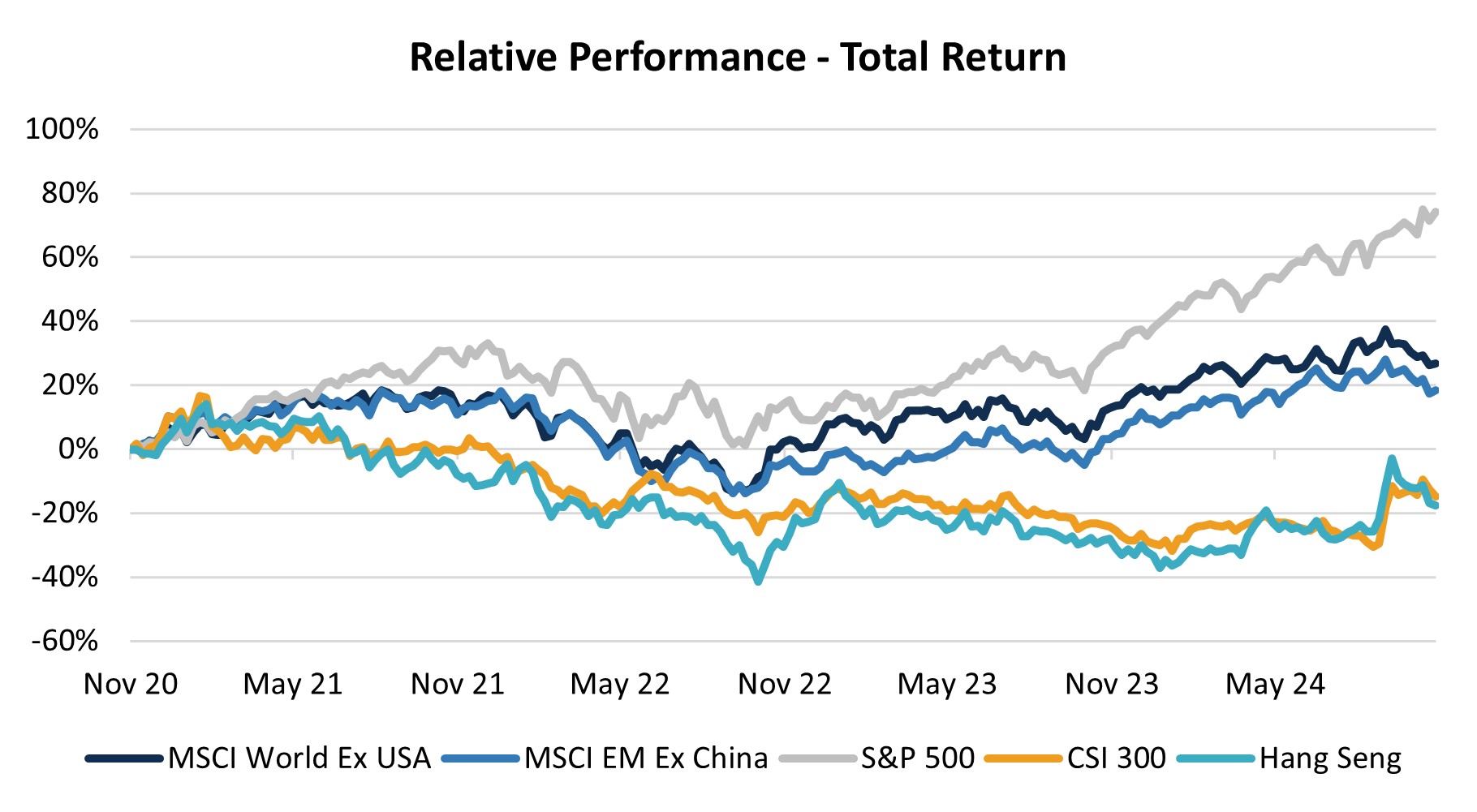

Against this challenging backdrop, sentiment towards Chinese equities has been under pressure. Economic concerns, geopolitical risks, weak corporate governance and lacklustre corporate earnings have led many to label China as “uninvestable.” These issues have been reflected in the underperformance in recent years and current low valuations of Chinese equities.

China’s relative underperformance in recent years

Source: Bloomberg, Total return in USD terms.

However, recent policy announcements have provided a much-needed boost to investor sentiment. Policymakers appear committed to placing a “floor” on economic activity, and further fiscal measures are expected to follow. We doubt Beijing would tolerate much weaker stock prices or a relapse in growth momentum. As the macroeconomic environment stabilises, Chinese equities – particularly onshore China A-shares – present a compelling investment opportunity.

China A-shares (listed on the mainland Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges) are domestically orientated with regards to revenues and investor ownership. This market differs from offshore China ‘H-shares’, which are traded in Hong Kong, and tend to be larger and have greater exposure to international markets and investors. Due to higher retail participation, China A-shares tend to be more volatile but are also more closely aligned with domestic economic trends.

We are constructive on China A-shares on a short-term cyclical basis, expecting sentiment to improve as economic activity finds a floor. Attractive valuations – coupled with anticipated policy support – underpin this view, while their domestic focus makes them less vulnerable to potential US tariffs or trade restrictions. Additionally, the strong retail ownership base suggests improving sentiment could drive significant upside potential.

However, for greater conviction in a longer-term strategic position, substantial progress is needed in addressing key headwinds. This includes the successful deleveraging of the property sector and a demonstrated commitment from policymakers to reaccelerate the economy rather than merely stabilising it. Critical to this effort will be substantial targeted fiscal stimulus, economic reforms, and other decisive measures.

China’s economic transition is a complex and challenging process, but it also presents opportunities for informed investors. Policymakers’ efforts to stabilise growth and navigate geopolitical headwinds will be crucial in shaping the country’s future. For investors, the key lies in identifying areas of resilience and growth within this evolving landscape.

Onshore China A-shares offer a compelling way to gain exposure to China’s domestic recovery while mitigating some of the risks associated with international trade tensions.

Please note, the value of your investments can go down as well as up.

This article provides information only and should not be interpreted as a personal recommendation or regulated investment advice.