Insight on ETFs

In this article, we examine ETFs in detail – including the risks – and explain why we believe they are a valuable addition to modern client portfolios.

What is an ETF?

An ETF is a collective investment scheme, typically formed as an open-ended investment company. They are listed and traded on a recognised stock exchange. Most ETFs are ‘passive’, in that they aim to track a market benchmark or index, for example an equity index such as the FTSE 100 Index or a bond index such as the iBoxx GBP Gilt Index.

Why have they become so popular?

ETFs typically offer a well-diversified and low cost means to gain exposure to the returns of a particular asset class, such as UK government bonds or Japanese equities. Unlike regular passive (or index) ‘tracker’ funds, they are also traded on an exchange at prevailing market prices. As they can be bought and sold at any time during market trading hours, they should offer more flexibility compared to traditional funds, which generally offer the ability to trade once a day. So not all passive funds are ETFs, but most ETFs are passive. Additionally, the fact that units of an ETF can be traded with other market participants, without the need for the underlying basket of stocks to be traded, allows lower costs of trading and higher liquidity.

Can ETFs ever outperform?

We would never expect the ETFs we hold to beat the returns of their target index, known as outperforming. However, we do expect them to track their index closely, and undertake ongoing due diligence to ensure we have selected the best strategy to do so. A well-constructed ETF should deliver returns that are very close to the index, less the total cost of investment in the fund. However, historic analysis (based on Morningstar data) has shown that active managed funds have struggled to outperform ETFs, once fees charged have been taken into account.

We found that the median UK equity fund investing in large companies underperformed a tracker fund by 0.85% p.a. in the three years to December 2017 after costs. This was fairly typical when looking at rolling three year performance periods starting 15 years earlier in December 2002. The outcome varied over time, but on average the median fund gave up 0.3% p.a. to the tracker.

Moreover, predicting which active funds are going to be the future winners is notoriously difficult. Again in the UK, evidence suggests that investors who selected funds which had ranked in the top 25% of funds over the preceding three years ended up with a fund that was in the bottom 25% of peers more often than one which stayed in the top 25% for the subsequent three years. This variation in active performance vs the predictability of passive performance has helped ETFs grow in popularity in recent years.

What do we look for in ETFs?

At Netwealth, we consider several key criteria when selecting the specific fund in which to invest for each asset class, regardless of whether it is through a regular fund or an ETF, including:

- The ‘fit’ of the fund’s underlying investments and benchmark index with the desired exposure within the specific asset class.

- How well the fund tracks its underlying benchmark index.

- The methodology being used to replicate the benchmark index, for example, whether it physically holds the underlying securities referenced by the index or if it uses a synthetic replication strategy.

- The total expense ratio (TER) of the fund, which represents the total cost of investing in the fund.

Understanding liquidity

In addition, when considering ETFs specifically, we look at the size and liquidity of the fund. All other things being equal, a larger ETF is preferable to a smaller one because the manager is less likely to restructure a successful fund. The liquidity of the ETF, by which we mean the ease with which it is traded, usually means that pricing behaviour will be less erratic and more aligned with the performance of the underlying assets. It is important for investors in ETFs to consider both primary market and secondary market (or ‘on-screen’) liquidity, which are not necessarily correlated.

Primary market

Discretionary managers and other institutional investors acting on behalf of clients will usually trade directly with ‘Authorised Participants’ of the ETF. They are called this because they are authorised to create and cancel units of the ETF as required by client demand, having already undertaken the required trading in the underlying securities which make up the exposures of the ETF. This process usually results in more efficient trading (ie at better prices) and ETF liquidity is closely aligned to that of the underlying market.

Secondary market

Secondary market liquidity, however, is directly dependent on how easy market participants, who are often trading in smaller sizes, expect to find selling units of the ETF on to one another. In this case, the ETF’s size and traded volume are key, but so is the nature of the underlying asset class – investors in a core asset class, like US equities, will expect that they will always be able to find future buyers, which may not be the case for a more niche market.

The importance of costs

Management fees

Many factors will affect an ETF’s ability to track its index, but the level of management fees charged by the ETF’s investment manager are likely to be a major driver of longer term relative performance. Lower fees and other costs will improve the ETF’s relative performance, all other things being equal – investors know this and pay close attention to how much they are charged. This, in turn, has driven the downward trend in ETF management fees through time.

Other costs and charges

Explicit management and administrative fees are not the only costs of investing in ETFs, however. Investors need to be aware of the implied costs that the ETF incurs when attempting to match the performance of its target index. These can be summarised as trading costs, and usually take the form of the spreads which ETFs pay when buying and selling constituent, underlying assets for the fund to reflect changes in the target index. These costs should be no more than those associated with regular funds which buy and sell securities more actively, but they will have the impact of detracting from fund performance. Where an ETF is constructed ‘synthetically’, the costs of the swap arrangement with a selected counterparty that delivers the desired index returns should also be taken into consideration.

Some costs can be offset by efforts known as securities lending. Here, the manager of an ETF agrees to lend underlying assets to a short-selling active investor in exchange for collateral. The interest received on the collateral is divided between the ETF and the manager on a pre-agreed basis, with the goal of increasing returns to both investor and manager. Securities lending can therefore be a useful way to improve the performance of an ETF – but it’s important for an investor’s due diligence to understand all the moving parts of this process. It’s also important to note that many regular, active funds participate in securities lending, too.

What are the risks of investing in ETFs?

There are some specific risks to note when investing via an ETF. Some of these risks are a function of using a passive approach to investing, and others are due to the wrapper itself. It’s important to understand, measure and mitigate these risks, some of which often get exaggerated by the financial press.

Tracking risk

When investing in ETFs, the primary risk on which most investors focus is the ability to track its target index. In this regard, a positive divergence in performance is as unwelcome as negative relative performance. Ideally, there will be minimal divergence in performance between the ETF and its target index over sustained periods of time to match investors’ horizons. Crucially, daily and weekly performance comparisons should also be considered to ensure that investors buying into and selling out of the fund at different points in time have confidence they will receive future market returns, and not be dependent on the date they invested.

In this way, an ETF’s tracking risk can be distilled into tracking difference (a longer-term measure which gauges the absolute magnitude of performance discrepancy between the ETF and its target index) and tracking error (a shorter term measure which gives a sense of the variability of relative performance). Low values for both are desirable. As shown in the graphic below, an ETF with a low tracking difference will not always have a low tracking error, and vice versa. At some point in any instrument selection process, a judgement call on preference between the two measures might be required.

Comparison of ETF tracking error and tracking difference

Source: Netwealth Investments

Model risk

Many factors will affect an ETF’s ability to track its index, but the level of management fees charged by the ETF’s investment manager are likely to be a major driver of longer term relative performance, as discussed above. However, the ability of the investment manager to match the performance of the target index also depends on their portfolio construction skills when attempting to replicate the behaviour of the target index successfully. So investors may also be subject to the model risk of the manager.

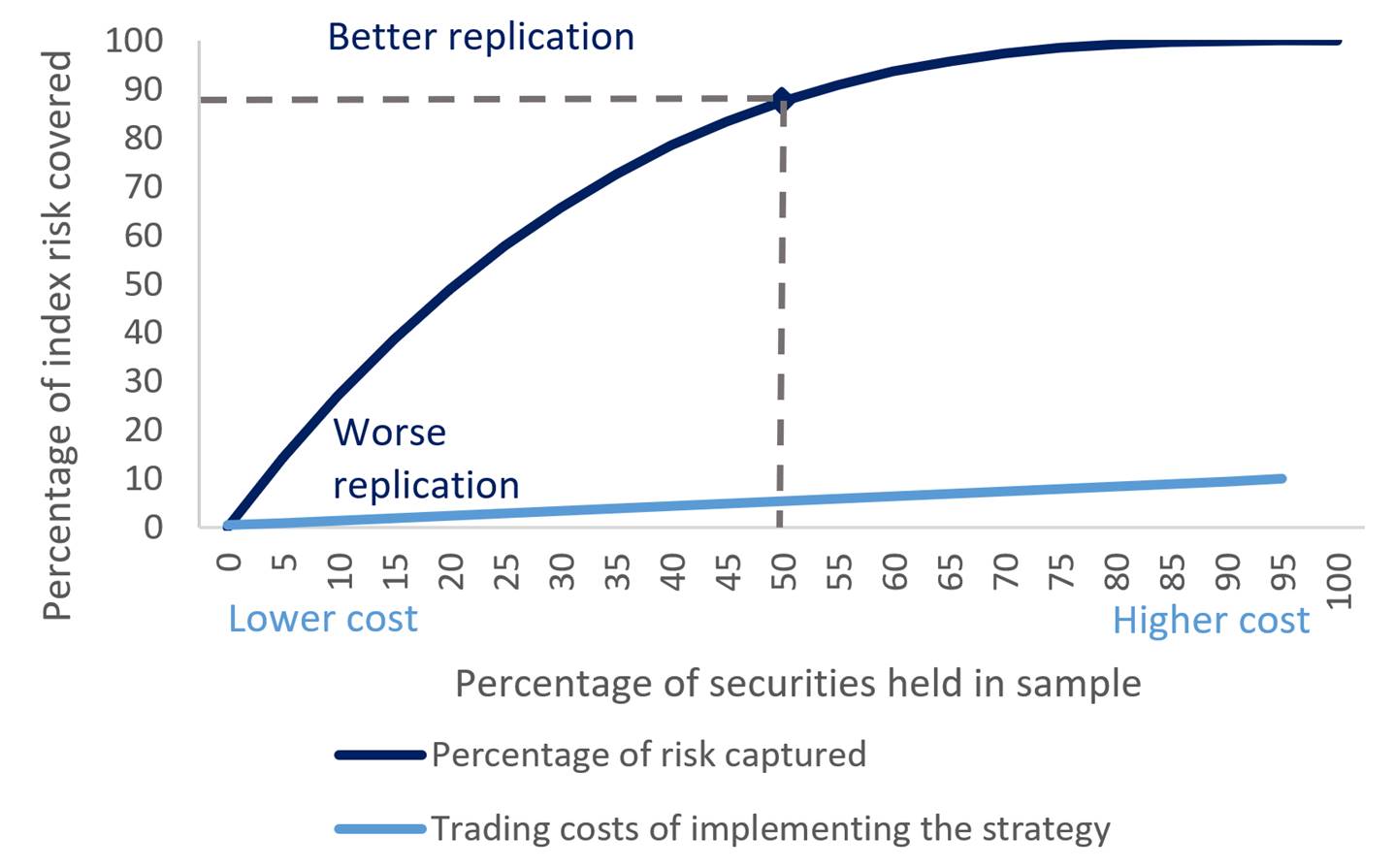

This is most relevant when a manager chooses to sample the universe of the index constituents, rather than replicate it fully. They would do this in a bid to reduce the trading costs required to fully mimic the target index, which may contain hundreds of different securities. A sampling portfolio manager will balance the desire to build a portfolio of representative securities – which will behave as close as possible to the target index – with an ambition to minimise the detrimental trading costs required to do so. The quality of a sampling model is particularly highlighted during periods when the ETF is seeing a large number of clients buying into, or selling out of the ETF.

Sampling methodology is important

Source: Netwealth Investments

Counterparty risk

In order to track the returns of the desired market index, an ETF will usually purchase the underlying securities that make up this index, just as most regular funds do. This is often referred to as being implemented ‘physically’. Alternatively, the ETF manager may enter into a contractual agreement with a third party (usually a bank) to exchange the returns from cash invested into the fund for the returns of the underlying market index it is aiming to track. The formal name for this transaction is a ‘swap’, as the two participants have agreed to swap one set of returns for another. An ETF that does this is often referred to as ‘synthetic’.

The performance of synthetic ETFs can therefore often track the performance of their target index more precisely than a physically backed fund is able to, because the swap is engineered specifically to do so. However, synthetic ETFs can carry additional risks of which investors need to be aware.

First and foremost is the counterparty risk the ETF is taking on behalf of its investors with the bank on the other end of the swap agreement. If the counterparty bank (which is often an affiliate of the ETF manager) gets into difficulty, and the broader market questions its ability to meet its obligations under such swap arrangements, then the traded price of the ETF will suffer and it will fail in its objective of tracking index returns.

To protect existing and potential clients under such a scenario, managers will provide collateral as a backstop to swap arrangements failing. As an investor, our responsibility is to ensure that we are happy with the counterparty risk, and the quality and size of the collateral posted. At Netwealth, our policy is to treat synthetic ETFs with extreme caution for this reason: there is an asymmetry of information between ourselves, the ETF manager and swap counterparty.

Systemic risk

The growth of ETFs has prompted some observers to worry about their potential to disrupt financial markets.

For example, there are fears that ETFs contribute to flash crashes, that some are ill-conceived, and can cause extra market volatility. We believe these attributes can be levelled at many securities, but accept that the popular use of ETFs among investors has amplified the potential impact of any event on the broader investment world – especially those which occupy the more exotic end of the investment universe. We are mindful to stay clear of these in any case.

Can you invest beyond passive ETFs?

In recent years, the ETF sector has developed beyond regular passive strategies, introducing approaches with varying levels of complexity and varying risks. This emphasises that the ETF structure itself is just a wrapper for investment strategies that investors find convenient, rather than the only way to access passive investment. At Netwealth, we have the scope to invest in all strategies which are deemed suitable for individual investors, but our core philosophy is to invest efficiently into straightforward strategies which provide predictable market exposure.

Below, we outline several of the more esoteric exposures which are accessible to investors through ETF structures:

• Leveraged and inverse ETFs. These aim to magnify or invert the performance of a given index on any particular day by using derivatives or borrowing. Most major indices – such as the FTSE 100 and Dow Jones – make leveraged ETFs available, which allow investors to double or triple the gains (but also magnifying the losses) of a chosen index. The risk here is that investors do not understand the methodology used to produce these results. A good case in point has been the recent, dramatic failure of several relatively small funds which were designed to offer the inverse returns of an index known as the ‘VIX’, itself a derivative of financial option prices for parts of the US equity market. Funds like these are complete anathema to our objectives at Netwealth, and we will never invest in assets with such layered complexity for our clients.

• Actively managed ETFs allow managers to diverge from their benchmark index as they feel appropriate – for example, by changing sector allocations or choosing different underlying components. By using such a strategy, however, there is no way of anticipating how much the actively managed ETF could differ from an index, thereby not giving investors the certainty of knowing up front what their risk profile or holdings may be.

• ‘Smart Beta’ is another phrase that has entered the financial industry’s lexicon in recent years, and broadly means ETFs which track indices which themselves have an actively managed component as they follow different index construction rules – rather than purely market capitalisation weightings. In this way, they have the ability to screen quantitatively for characteristics which are expected to improve performance, such as fast-growing corporate earnings or on different valuation metrics to produce a basket of stocks which are cheaper than average.

Our view is that these strategies are helpful to have in a manager’s toolkit, but they may come with higher associated costs and investors have to understand the subjective inputs to index construction; they can almost be seen as a half-way house to active management, so caveat emptor.

Will ETFs underperform in ‘bear’ markets?

A favoured opinion from proponents of active management is that they will outperform passive managers during a downturn. However, the data does not support such an argument.

While there are periods when active managers outperform passive investment portfolios in aggregate, it is extremely difficult to predict when this will happen (a task similar to trying to time the market). In our view, it is too simplistic to expect that a falling market will favour active managers.

Indeed, during the financial crisis, less than half of UK active funds outperformed* – between June 2007 and March 2009, only 45% of active UK equity funds outperformed index tracking funds. Moreover, picking the individual managers that will outperform in a coming downturn is even harder. So, investors have to predict the market fall and then find the right manager. Against a backdrop of very poor persistence of outperformance, and the challenges of finding a manager who will consistently outperform markets in different environments, it’s no surprise that such strategies often end with disappointment.

Conclusion

It’s important to focus on what ETFs represent. They aren’t a new asset class to be scared of, but another tool that can be used with discretion to optimise client performance outcomes and improve transparency of their investment portfolio.

* Based on Morningstar data.

Please remember that when investing your capital is at risk.